We are all getting older every day. Even the young get old (please don’t repeat this widely; some of your friends will think you’re losing it). As this happens, many of us try to hold on to youth through various means. Increased visits to our physicians, more time doing exercise, watching what and how much we eat all are efforts to maintain health for as long as possible. Many of us, young and old but particularly as the sun gently sets over the horizon, take a variety of health supplements. Whether various of these substances do any good is a hotly debated matter by, on the one hand, the medical research community and on the other, the supplement industry and advocates for less drug-and-surgery-based interventions.

While this is completely understandable from a purely human point of view, there are various important factors that consumers should understand about the way the supplement and pharmaceutical industries are regulated.

In 2013, a market analysis reported that the global market for vitamins, minerals, and nutritional and herbal supplements (VMHS) was around $82 billion annually and was predicted to grow to $107 billion by 2017. Consumers in the U.S. represent about 28% of that market. Of course, the pharmaceutical industry revenues were around $1.2 trillion in 2014 and are expected to grow to $1.6 trillion by 2018-that makes the pharmaceutical industry about 20 times as large in terms of revenue. On the other hand, costs for the pharmaceutical industry are huge. It takes about $2.9 billion to develop a drug through to full approval by regulatory agencies and takes roughly ten years—often more—to develop any successful drug candidate from identification of a molecule with activity to post-marketing study completion. This does not include sales and marketing costs (advertising, pharmaceutical sales) that are often expensive and consistently are under pressure from regulators to behave more ethically. From identification of a possible chemical structure to successfully obtaining marketing permission from a regulatory agency, only about 5 in 5,000 possible drug candidates make it through the entire process; this is only 0.1% of the drug candidates that start out. This percent is likely to go down as (1) more biological drugs are developed for (2) increasingly rare diseases.

As most VMHS products are naturally-occurring substances that are inexpensive to manufacture in bulk quantities, as no pre-clinical or clinical studies of any kind are required to place them on market, and as little testing is required at any point in the manufacture-to-consumer supply chain, the cost vs. revenue math for supplements is significantly different.

At the end of the day, we all need to make our own decisions about what we are going to do with our personal health. The following material may help you decide whether supplements are appropriate for your desired outcomes.

VMHS market size: https://www.mckinseyonmarketingandsales.com/sites/default/files/pdf/CSI_VMHS_FNL_0.pdf

Pharmaceutical market size: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/Life-Sciences-Health-Care/gx-lshc-2015-life-sciences-report.pdf

Cost of drug development: http://csdd.tufts.edu/news/complete_story/tufts_csdd_rd_cost_study_now_published

Identity:

The chemical formula or herbal source of any pharmaceutical or supplement is the at the core of the issue. If you have Type I diabetes mellitus, you will be prescribed insulin, which is a specific protein with a specific chemical structure and formula depending on its source (e.g. human, bovine, porcine, genetically engineered). While it is injected in an aqueous buffer with some stabilizers, every component of the injection is checked numerous times during the manufacturing process to make sure that nothing but insulin, water, the buffering salts (which hold the water within a specific human pH range), and the stabilizers all have to be present in very specific amounts and nothing else must be in the injection above a certain very low tolerance. If insulin is not present, patients may suffer and may die. If contaminants are present, either carried through from improperly sourced raw materials (e.g. water, salts) or introduced through inadequately cleaned equipment, patients may suffer or die. These outcomes could have an enormous reputational and financial impact on the manufacturing company. Additionally, worldwide regulatory agencies are required to audit manufacturers and determine if they are following best practices for material sourcing, checking material quality, equipment cleaning, and checking the final product, all the way through packaging and storage pre-shipment. It is a complex and meticulous business that requires a large team working together to ensure that patients get the appropriate product.

So, the identity of the product—the insulin in the above example—is very important but every component that enters the diabetic’s body is checked almost as much at various stages in the process.

So, the identity of the product—the insulin in the above example—is very important but every component that enters the diabetic’s body is checked almost as much at various stages in the process.

In general, identity in supplements splits into two categories: (1) items that are distinct chemical entities, whether inorganic (calcium, trace metals such as copper, selenium, molybdenum, other minerals) or organic (vitamin C, vitamin B12, riboflavin, vitamin A, niacin, vitamin E, etc.) and (2) herbal supplements (echinacea, ginseng, saw palmetto, St. John’s wort, yohimbine, black cohosh, ginkgo biloba, etc.), which start life as plants, are harvested and preserved in some manner.

I take a multivitamin every morning, in spite of numerous research studies that indicate this is probably not necessary if my diet is relatively healthy (it is but I am a recent convert to a vegetarian diet). My particular multivitamin contains the following chemical items: vitamin A, C, D, E, K, thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, B6, folic acid, b12, biotin, pantothenic acid, calcium, phosphorus, iodine, magnesium, zinc, selenium, copper, manganese, chromium, molybdenum, chloride, potassium, silicon, lycopene, lutein, boron, vanadium, nickel. Each one of these has a weight or international unit (IU; this has to do with the biological activity or potency of the dose provided) associated with it. Along with some of these vitamins, there is a counterion, which makes the mineral (in particular) a salt form. These are not typically considered to have any important supplementary properties (e.g. magnesium oxide; the oxide does not have any claimed importance in the supplement), although in some cases the counterion is specifically used to impart some supplementary material (e.g. calcium phosphate; both ions are used by our physiology). In addition to these vitamins and minerals, there are excipients, which are the materials that help all of the “active” ingredients hang together, remain stable on the shelf for some specific time, and form easily into a pill. In the case of this multivitamin, the excipients include: cellulose gel, starch (corn & tapioca), hypromellose, croscarmellose sodium, silicon dioxide, gelatin (porcine), and polyethylene glycol. These do not have weights or IUs associated with them but the overall formulation of the pill is an exact science called pharmaceutics. Once a formulation is determined, it is best for the manufacturer to hold to the formulation as the quality of the pills will remain within specified ranges. This means that they will not turn to dust in the bottle or spoil early or break too often during shipping, thus leading to return customers.

There is a new category of supplement known as “USP Verified (uspverified.org). The United States Pharmacopeia Convention is a reputable organization that has assisted the U.S. regulatory authority in assuring the identity and purity of pharmaceuticals for decades. They have recently expanded their scope to assist some supplement companies in verifying the identity, purity, and amounts of vitamins and other supplements available on the market. A very limited number of supplement companies have signed up to participate in this service (you can go to the above website to see what products are covered).

While it is not certain that other supplement manufacturers do not follow appropriate controls, the only “good” reason that some don’t is because it is costly and therefore consumes a bit of profit.

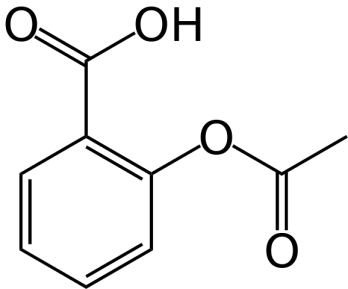

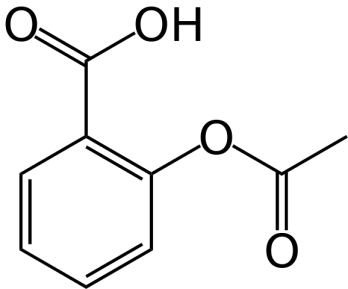

In the pharmaceutical arena (which has many detractors, but not for this reason), the company must submit documentation that the medicine they have researched, developed and are selling has the unique chemical structure of that medicine. For instance (and to make this simple), aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) must have the following structure as proven by several common, validated analytical tests:

Another way of saying this is that for each compound, it must have the exact number of carbons, hydrogens, oxygens, nitrogens, sulfurs, etc. in the exact interrelated positions as are unique to that chemical compound.

Another way of saying this is that for each compound, it must have the exact number of carbons, hydrogens, oxygens, nitrogens, sulfurs, etc. in the exact interrelated positions as are unique to that chemical compound.

There is some evidence that some supplement products do not include the chemical compounds (vitamins and minerals) listed on their label or that the substances are present but not in the specified weights listed. The consumer is consuming something pill-shaped but what is it? It may be that the consumer is enjoying a pill-shaped item that is mostly substances that have been tested extensively over the years and are “generally regarded as safe” (GRAS) materials. There are many categories of these materials, which are lumped together under the term “excipients.”

There are ongoing studies being performed by the Center for Biodiversity Genomics at the University of Guelph and at other academic centers around the world which attempts to identify the contents of herbal supplements. These supplements should simply be a preserved form of leaf, root, bark, etc. from some plant for which some ancient beneficial property has been observed. Many cultures from around the planet have used these types of materials, usually directly from the plant in question, for centuries, if not millennia. In some cases, benefits have been seen in some patients (the dead ones aren’t around for a discussion). In many cases, an herbal supplement may fit the old “snake oil” profile: “Good for What Ails You!”

Willow bark, for instance, has some pain, inflammation, and fever relief efficacy (it contains the raw material salicin, which is metabolized to become salicylic acid). If we were to purchase a substance called “willow bark” for the purposes described above, we would have a reasonable expectation that the willow bark would (1) be willow bark and (2) contain salicin. A lot of the studies being performed using DNA sequencing have demonstrated that the herbal supplement industry sometimes sells products labeled very specifically to contain a plant substance that does not contain the plant’s DNA (and is, therefore, not the plant) and does not contain the substance known to provide the desired medicinal effects. This is a type of fraud. It will only disappear if consumers demand more from their supplement providers.

Here are some references for further reading:

http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/02/how-supplements-work/385119/

http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1741-7015-11-222.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3216529/pdf/srep00042.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22970567?dopt=Abstract&holding=f1000,f1000m,isrctn

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4882080/

https://bmccomplementalternmed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12906-016-1086-0

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S096399691200292X

http://bsh.ahpa.org/SampleHerb1.aspx

http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/2012/05/multivitamins/index.htm

http://apps.who.int/prequal/trainingresources/pq_pres/workshop_China2010/english/22/002-Excipients.pdf

Purity:

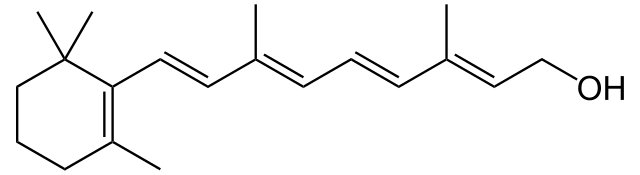

For each medicine or excipient, testing has to be performed to ensure that it is reasonably pure. Well, that sounds like an odd thing to say – “reasonably pure.” What does that mean? The FDA has established criteria that require a medicine to be pure from synthesis by-products (solvents, starting materials used in the synthesis, side products that are not the medicine, impurities that may be introduced during the manufacturing process from equipment used). If the drug is dosed at < 2 g/day, the threshold for reporting any impurity is 0.05%. The impurities must be chemically identified if any one of them is above 0.10%. This adds cost to development and is a significant driver for why quality control procedures are in place throughout manufacturing to ensure purity. They must be qualified (i.e. understood for toxicological and/or pharmacological purposes) if they rise above 0.15% or 1.0 mg/day, whichever is LOWER). When it gets to doing toxicological and/or pharmacological tests, the expense goes up really dramatically! If these are the criteria for drugs, shouldn’t they apply to supplements? I believe so. If you take something labelled “vitamin A,” you should have a reasonable expectation that 99.95% or more of that supplement product is vitamin A, as characterized by its chemical structure:

The excipients used should all be pure as well.

Obviously, material with lower purity profiles are less costly. If a manufacturer were to purchase bulk CMC to formulate in with the vitamin A, it should be reasonably free from impurities as characterized above. If a manufacturer were to use 95% pure carboxymethylcellulose (CMC), it would probably cost less than 99.5% or 99.95% CMC. In several of my previous jobs, I had to purchase gases for analytical purposes (hydrogen and nitrogen most commonly). If I purchased 99.9% pure nitrogen it would cost a bunch more than 99% pure nitrogen. Same applies to GRAS excipients. Is this testing done? It may or may not be. The supplement manufacturers do not fall within the purview of the FDA, so they do not need to prove their purity during an initial application for approval for marketing, nor do they need to prove this on a batch-by-batch basis during manufacturing.

One very important aspect of good manufacturing practices (cGMP) is something called cleaning validation. For medicines, all equipment that touches a drug or excipient must be cleaned between batches. The manufacturer must test the equipment after a validated cleaning procedure has been completed. The equipment must be tested for residual cleaning products (soaps, bleach), bacteria, fungi/molds, solvents, drug, excipients, etc. Is this done in the supplement arena? I don’t know and they don’t have to prove they do this. Their only limitations are consumer-driven, e.g. do consumer’s health see a negative effect after taking their supplements or not?

For further reading: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm073385.pdf

Stability:

Another factor is how long the supplement (or drug) retains its optimal purity after it has been manufactured. All chemical compounds, including the salt forms of minerals (calcium chloride), interact with other materials in the environment, principally water (humidity), oxygen (it’s all around us) and light (various wavelengths of light, particularly ultraviolet light from sun can change the structure of chemicals) through various chemical mechanisms. Drug companies test stability properties of drug substance (the active ingredient) and drug product (the pill or injectable, etc.) for months and years during research and development and create strategies to optimize the drug stability (for instance, store insulin in a refrigerator). Supplement manufacturers are not required to do this testing, although some may. When products degrade over time, they create a different kind of impurity called a degradant. These are chemical substances that are related to the drug, supplement or excipients that no longer have the properties for which the product was purchased. There are limits to how long a product should be used (usually it is months, sometimes years) after purchase. The consumer has significant responsibility here. How often does a household keep a partially used medication or supplement for over a year or more and then use some? While it is “probably” not going to do significant harm, it is no longer the product that the manufacturer has tested and provided as approved by the FDA.

So, if you are in the habit of sometimes using supplements, then not using them and so on, keep an eye on the expiration date. If you have been keeping them in the dark at normal household temperatures (between 20⁰C and 25⁰C), you’re probably okay to keep using them for a couple of months or so after the expiry date as this date is probably set for an average case scenario. This does NOT apply if you are taking a biological like insulin. If you are taking an herbal supplement, it is difficult to know if (1) the marketed herb is in the bottle, (2) any stability testing was done on how long the herb will remain effective, and/or (3) whether what’s in the bottle will have the desired effect in the first place. Figure out what you need to do to increase the probability that the marketed herb is in the bottle and follow the expiration date advice, if it exists.

Amount:

I touched on this in the “Identity” section above, but it may bear repeating. On any medicine or supplement, there are markings that indicate how much of the active material is contained in a dose (ibuprofen=200 mg/tablet; vitamin C=500 mg/tablet; etc.). Drug companies are held to high standards, above and beyond the purity and stability criteria listed above. Do supplements actually contain the amount of substance that is indicated? We do not always know. Some testing indicated above in the references indicate that in some cases, there is little to none of the labelled substance in the product sold.

Batch-to-batch equivalence and product-to-product equivalence:

Once one batch of medicines is completed, it must be tested to ensure that it meets all the manufacturing criteria as listed above, but each additional batch manufactured must also meet those criteria.

Additionally, when a generic drug manufacturer creates their product, they must prove it is equivalent through extensive in vivo testing (testing in “normal healthy volunteers” or clinical trial participants) to the product made by the company that initially patented the drug. Do supplement companies do either of these kinds of testing? Does one supplement manufacturer prove that their vitamin C is identical to all other vitamin C products available? No. The upshot of this is that while all of the products are labelled “vitamin C,” one product may deliver more or significantly more than the labelled amount, while another delivers less or significantly less. There is a bit of a rocky comparison here: the innovator drug company has created a unique chemical product for the first time, while the supplement company is taking a compound that is found in nature and creating a product. The bottom line remains the same though – any supplement user would probably like to know that the product they are taking is delivering something reasonably close to the labelled amount of the substance and that this is true for each bottle of supplement they purchase from the manufacturer, regardless of batch or time of manufacture.

Pharmacological Effect:

When a medicine is developed it must show a target pharmacological effect within a statistically significant range above placebo or in the range of similar medicinal therapies; developing drugs with a statistical response below similar medicinal therapies is increasingly seen as not worthy of the enormous expense and time involved in drug development. The studies are done following a variety of complicated and statistically robust clinical trials in (1) normal healthy volunteers when the drug is considered sufficiently safe to allow this (many cancer drugs have toxicity profiles that do not allow dosing in anyone but patients) and/or (2) patients who have been diagnosed with the target illness so that the efficacy of the therapy can be evaluated. Often, the trials are doubly blinded so that the physician and the subject/patient are unaware whether they are receiving a medication or not until after the trial is completed and the results are unblinded. By the time a medication is approved by a regulatory agency it has been dosed in thousands of subjects and patients. All effects, positive and negative (adverse events) are tabulated and are provided to the public (e.g. the horrifying list of often minor potential effects heard on TV ads). Supplements rarely, if ever, go through this kind of rigorous testing. If they are tested in this manner, it is usually by academic centers that want to determine if there is anything to the efficacy claims often cited on various supplement-promoting websites.

There is a particular kind of correlation that is studied. It is called the dose-response curve. A single dose or multiple dose regimen is followed – the dose amount (milligrams, for instance) is the known portion of the experiment. The peak concentration in blood and other fluids is studied over many subjects and patients. In the case of multiple doses over many days, the steady-state concentration is determined. The follow-up pharmacological and physiological data is studied; what effect has the drug had on desired and undesirable outcomes? Is blood pressure lowered (if that is desired) or elevated (usually undesirable)? Are liver enzymes constant (usually desired) or do they change (usually undesirable)? Is mood altered, in the case of psychiatric medicines, in a manner that is desirable or not? Is a tumor reduced in size, and if so, are any side-effects minimal in comparison to the improved health of the subject?

In the case of supplements, the same relationships are often claimed (e.g. reduces free radicals in the bloodstream and tissue (vitamin C), improves prostate health (saw palmetto), improves energy (whatever that means), etc.). These are measurable “endpoints” or results in some way, so why aren’t they measured? The primary reason is that it is costly to do so with the same rigor as the pharmaceutical companies must demonstrate. The secondary reason is that very few of the supplement companies actually own the substance they are selling (e.g. vitamin C or saw palmetto), so they cannot patent the substance itself (pharmaceutical companies have a 20-year patent from the time they list the patent with that agency – and that is YEARS before it is approved or marketed). One way supplement companies get around this is they come up with combinations that are “unique” to their firm, but even in these cases, the substances in the product are not unique and another company could come up with a copy of that product if they have sufficient information. Or they could make up a similar product; as there is no requirement for the supplement company to prove pharmacological effect, there is no real reason for any company to copy another manufacturer’s blend.

Cases where the supplement companies get in trouble:

Probably the biggest example of this is with the ephedrine (e.g. ma huang or ephedra) situation a decade back.

http://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/ephedra–ma-huang/background/hrb-20059270

Another is colloidal silver as a homeopathic therapy.

https://nccih.nih.gov/health/silver

Cases where pharmaceutical companies get in trouble in spite of regulations:

Johnson and Johnson had one of their manufacturing plants sidelined because of inadequate quality control (i.e. testing of the drug substances and products they were manufacturing).

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/07/22/AR2010072206169.html

Several Indian manufacturing plants that export generic drugs to the U.S. have been sidelined.

http://www.raps.org/Regulatory-Focus/News/2015/11/09/23562/FDA-Form-483s-From-India-A-Deep-Dive-Into-the-Problems/

While not an actual pharmaceutical company, this pharmacy compounding company made a product contaminated with a fungus that caused numerous deaths:

http://www.cdc.gov/hai/outbreaks/meningitis.html

https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/compounding-pharmacy-linked-to-meningitis-outbreak-knew-of-mold-bacteria-contamination/2012/10/26/6e3344ee-1fa0-11e2-afca-58c2f5789c5d_story.html

Compounding pharmacies are not held to the same manufacturing standards as manufacturers (although these (as above) can do the wrong thing as well). The FDA is trying to establish a uniform set of regulations to ensure that this does not continue to be a problem: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Testimony/ucm327667.htm

Conclusion

The bottom line is that it is all about money. If a company does all the types of testing I’ve alluded to their costs are higher than if they do only some or no testing. Supplements aren’t cheap. If you go to your pharmacy or grocery store (or supplement store for that matter), all the products of a particular type cost roughly the same, although the ones in supplement stores are almost always more expensive. Who made these pricing decisions? Are you paying for the same type of testing for all the products or not? Honestly, no one except the companies themselves know. It’s even difficult to tell whether they ask themselves these kinds of questions.

So how, you might ask, does the supplement industry get around being more diligently regulated? They are putatively healthcare-related products, aren’t they? The consumers are going to place them inside their bodies and hope for results, aren’t they? Yes and yes. The answer is that the supplement industry has a very powerful lobby and this lobby makes sure that the U.S. Congress does not pass legislation to regulate it. Congress gets paid, in some clandestine way, to ensure that consumers are not protected in the same way they are with pharmaceuticals. That is just wrong.

http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2014/06/john-oliver-explores-the-real-reason-for-americas-problem-with-magic-supplements/373228/

http://time.com/3741142/gnc-vitamin-shoppe-supplements/

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/06/opinion/the-politics-of-fraudulent-dietary-supplements.html?_r=0

http://www.cbsnews.com/news/dietary-supplements-latest-government-uproar-no-match-for-industry-lobbying-money/

As a consumer, should we be more interested in what profit our supplement companies are banking or should we be concerned about what we are putting in our bodies and why. I’ll vote for the second criteria. I wish more people understood the applicable criteria so that they would demand appropriate testing and quality control standards as well.

Here is peer-reviewed articles on the dubious benefits of supplements, although there are important reasons to follow your doctor’s recommendations if (1) your diet is not normal for some reason or (2) you are pregnant.

http://annals.org/article.aspx?articleid=728199

The bottom line?

Test

So, the identity of the product—the insulin in the above example—is very important but every component that enters the diabetic’s body is checked almost as much at various stages in the process.

So, the identity of the product—the insulin in the above example—is very important but every component that enters the diabetic’s body is checked almost as much at various stages in the process. Another way of saying this is that for each compound, it must have the exact number of carbons, hydrogens, oxygens, nitrogens, sulfurs, etc. in the exact interrelated positions as are unique to that chemical compound.

Another way of saying this is that for each compound, it must have the exact number of carbons, hydrogens, oxygens, nitrogens, sulfurs, etc. in the exact interrelated positions as are unique to that chemical compound.